Marburg virus disease (MVD) is a rare but highly lethal zoonotic infection that continues to pose a serious public health threat. Although outbreaks are relatively infrequent, historical data show that when Marburg virus emerges, it can have devastating consequences for individuals, communities, and health systems. Understanding patterns of cases and deaths over time provides important insights into how preparedness, surveillance, and response can be strengthened through a One Health approach.

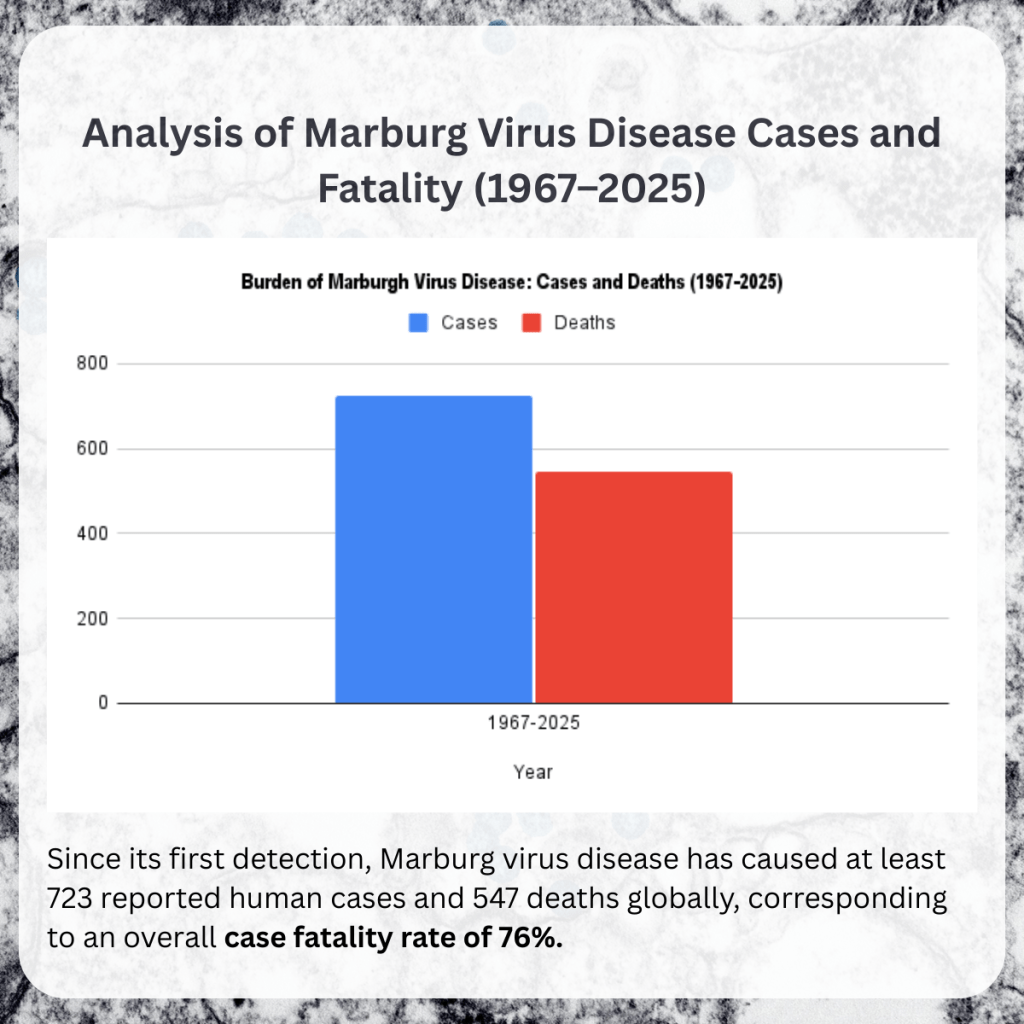

Since its first identification in 1967, Marburg virus disease has resulted in 723 reported human cases and 547 deaths globally, corresponding to an overall case fatality rate (CFR) of approximately 76%. This exceptionally high fatality rate places Marburg virus disease among the most severe viral infections known to affect humans. While advances in clinical care and outbreak response have improved outcomes in some settings, the disease remains a critical concern, particularly in parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

Patterns of Outbreaks and Severity

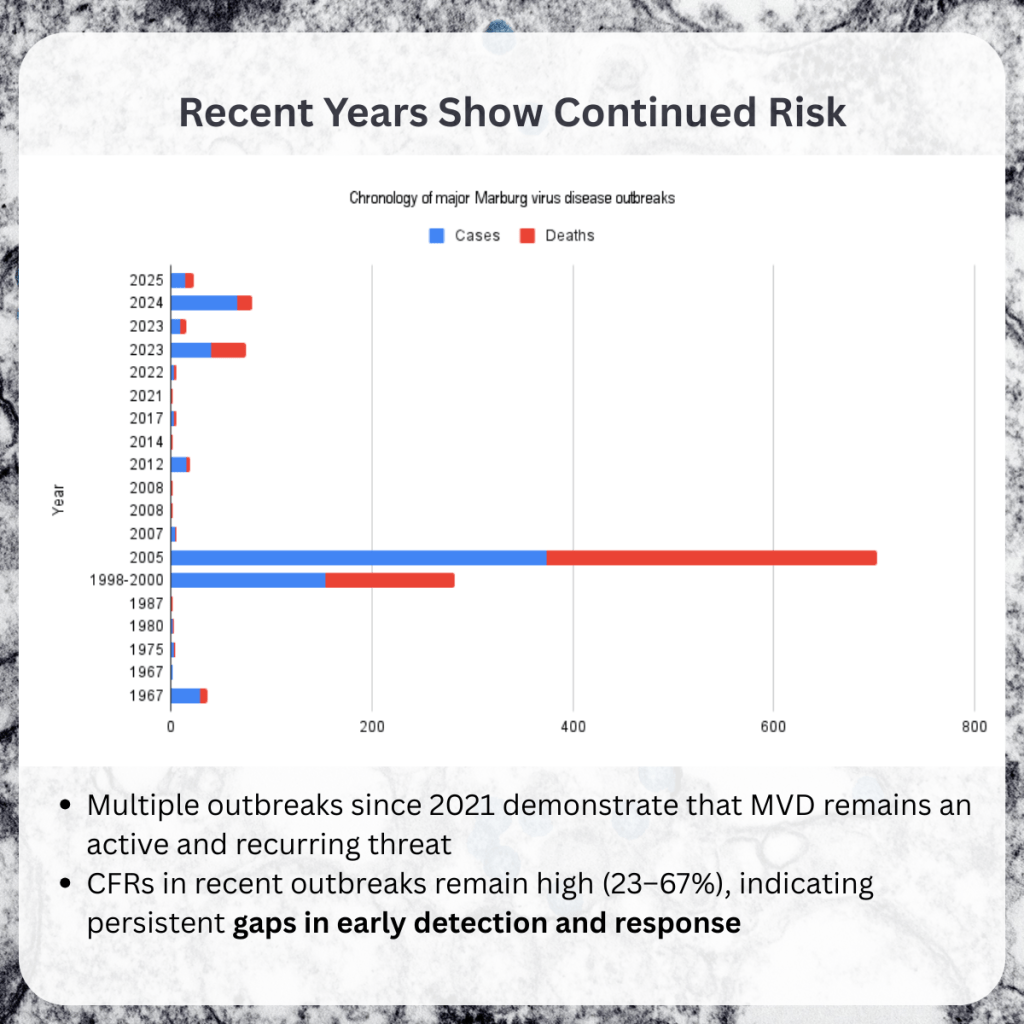

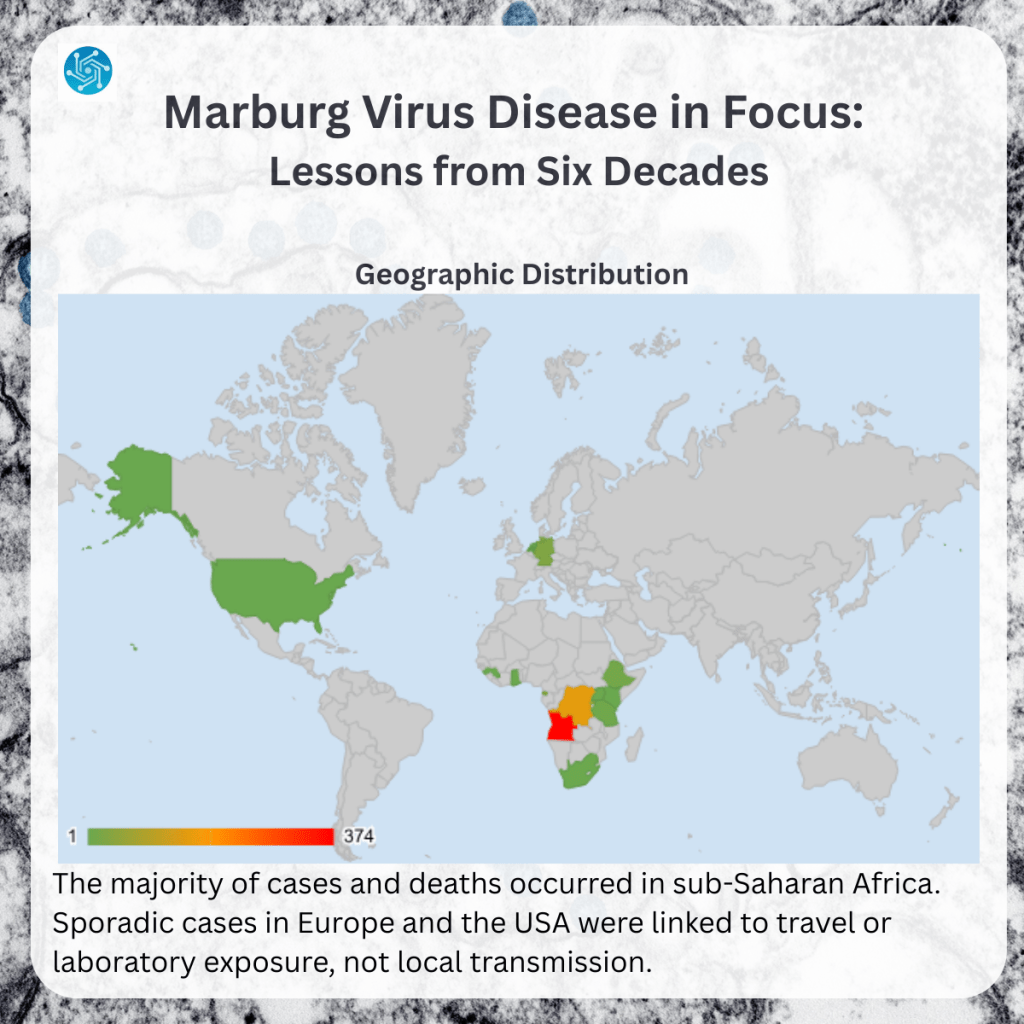

Analysis of historical outbreaks shows that the burden of Marburg virus disease is not evenly distributed. A small number of large outbreaks account for the majority of reported cases and deaths. Notably, the 2005 outbreak in Angola alone recorded 374 cases and 329 deaths, representing more than half of all deaths documented globally. Similarly, the 1998–2000 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo resulted in 154 cases and 128 deaths.

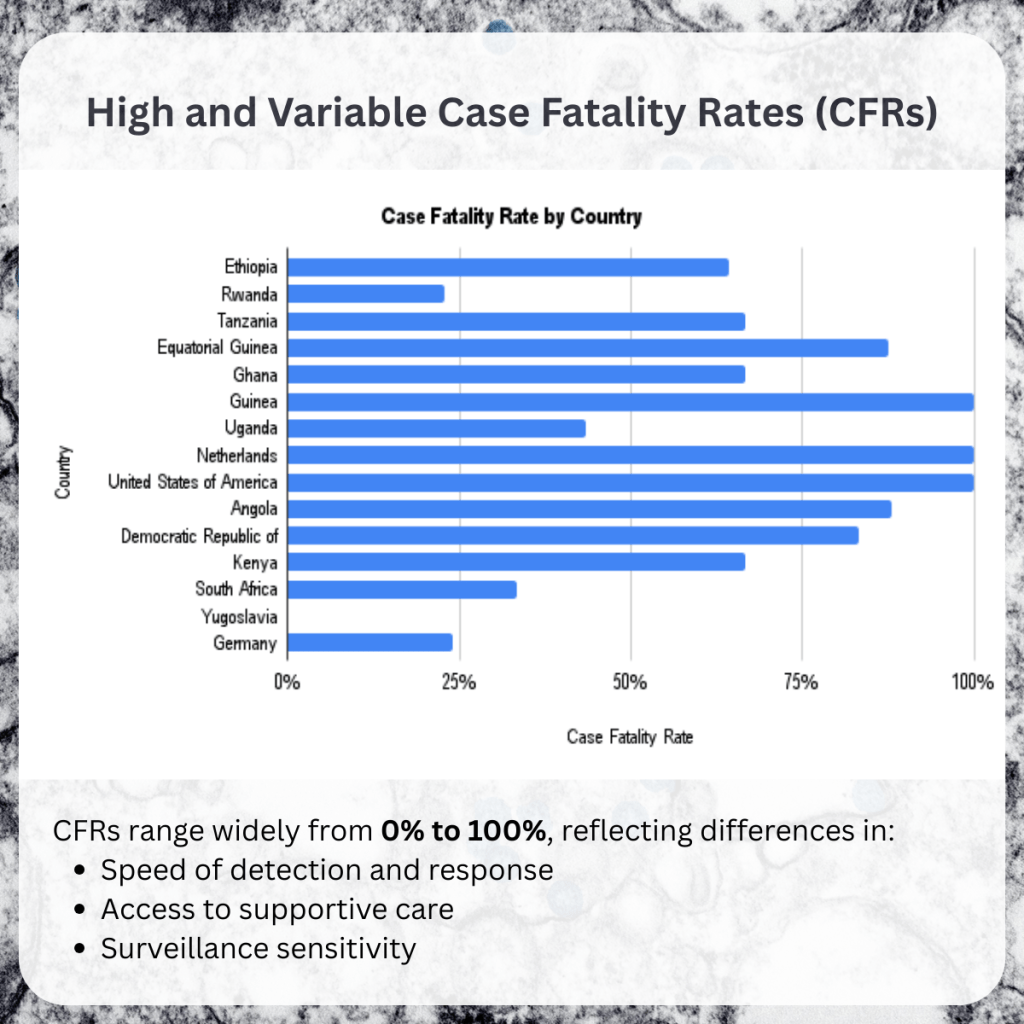

In contrast, many other outbreaks involved only a few cases, often with very high or even 100% case fatality rates. These small outbreaks frequently occurred in contexts where detection was delayed, clinical suspicion was low, or access to supportive care was limited. Together, these patterns highlight how early recognition and rapid response can significantly influence outcomes.

Geographic and Zoonotic Context

The vast majority of Marburg virus disease outbreaks have occurred in Africa, particularly in countries such as Uganda, Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Ethiopia. Sporadic cases reported in Europe and North America were linked to travel or laboratory exposure, rather than sustained local transmission.

Marburg virus is a zoonotic pathogen, with fruit bats (Rousettus species) identified as its natural reservoir. Human infections are thought to result from contact with infected bats or environments contaminated with bat secretions, followed by human-to-human transmission through direct contact with bodily fluids or contaminated materials. This ecology underscores the importance of understanding animal reservoirs, environmental drivers, and human behaviors that create opportunities for spillover.

Recent Outbreaks: A Persistent Risk

Outbreaks reported between 2021 and 2025 in Guinea, Ghana, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Ethiopia demonstrate that Marburg virus disease is not a historical concern but an ongoing and recurring risk. Case fatality rates in these recent outbreaks ranged from 23% to over 60%, suggesting some improvements in detection and care, but also highlighting persistent vulnerabilities.

The recurrence of outbreaks across multiple countries points to shared challenges, including gaps in surveillance, limited diagnostic capacity in peripheral health facilities, and delays in recognizing unusual clusters of severe illness. These challenges are compounded by weak links between human health, animal health, and environmental monitoring systems.

One Health Implications

Marburg virus disease provides a clear example of why One Health approaches are essential. Preventing and controlling outbreaks requires coordinated action across sectors: wildlife surveillance to understand viral circulation in bat populations, environmental monitoring to identify high-risk settings, and strong human health systems capable of early detection and rapid response.

Integrated surveillance systems that link animal, environmental, and human health data can provide early warning signals before outbreaks escalate. Equally important is investment in infection prevention and control (IPC), particularly in healthcare settings, where transmission risks are highest for health workers and caregivers.

The Role of Capacity Building and Risk Communication

Beyond surveillance and clinical care, capacity building and risk communication are critical to reducing the impact of Marburg virus disease. Health workers need training to recognize suspect cases early, apply IPC measures consistently, and communicate risks clearly to patients and communities. At the community level, trusted, culturally appropriate communication helps reduce fear, stigma, and misinformation—factors that can undermine outbreak response.

Strengthening competencies in outbreak preparedness, community engagement, and cross-sector collaboration is essential for translating One Health principles into practice. Investments in people, systems, and communication are as important as investments in laboratories and surveillance technologies.

Conclusion

Although Marburg virus disease remains rare, its high lethality and repeated emergence make it a priority for preparedness efforts. Historical data show that outcomes are strongly influenced by how quickly outbreaks are detected and how effectively sectors work together. By applying a One Health lens—integrating surveillance, building workforce capacity, and strengthening risk communication—countries can reduce mortality, protect health workers, and prevent small outbreaks from becoming major public health crises.

References

World Health Organization (1 December 2025). Disease Outbreak News; Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON589

Leave a comment